Dame Jane Goodall, who has died aged 91, spent a lifetime in close study of the chimpanzee and in the process completely transformed man’s understanding of his nearest relation; her work was described by the writer and biologist Stephen Jay Gould as “one of the Western world’s great scientific achievements”.

Valerie Jane Goodall was born in London on April 3 1934. Her father, Mortimer Morris-Goodall, was an engineer, her mother Vanne, née Joseph, a novelist. She was not yet two years old when her mother gave her a toy chimpanzee which she named Jubilee. “I cannot remember a time when I did not want to go to Africa to study animals,” she recalled in 1963. When she was five the family moved to Bournemouth and young Jane attended the nearby Uplands School.

Although good at her studies, she preferred learning about animals and playing out of doors, and was once discovered sleeping with earthworms under her pillow.

On leaving school she worked as a secretary at Oxford University, and as an assistant editor at a film studio in London. A school friend then offered her a holiday at the family home in Kenya – at which chance Jane Goodall jumped. She set sail for Mombasa in 1957, aged 23.

Having holidayed, she set off for Nairobi in search of Louis Leakey, the paleontologist who was, with his wife Mary, trying to prove his (then controversial, now generally accepted) theory that man originated in Africa, and not Europe or Asia. Leakey gave Jane Goodall a job on the spot as his assistant secretary.

Leakey also held the unpopular belief that study of the great apes would yield important insights into the behaviour of early man. With this in mind he had located a group of chimpanzees living on the shores of Lake Tanganyika; he suggested that Jane Goodall begin a long-term study of the chimps. “He wanted,” she recalled, “to send someone whose mind was uncluttered and who had endless patience. Of course I accepted.”

The authorities would not allow a young Englishwoman to live alone in the bush, so she brought her mother along. After extensive reading on chimpanzee behaviour, Goodall mère et fille arrived at what is now the Gombe National Park in July 1960.

Paying no attention to predictions that she would never get near the apes, Jane Goodall trudged off each morning to study the animals. For two months the chimps fled at her approach but when she discovered a clearing, 1,000 ft above the lake, she found that she could observe them from a distance, and their curiosity began to get the better of their fear. They soon grew accustomed to “this peculiar, white-skinned ape” sitting quietly among them every day from dawn to nightfall.

Their behaviour, despite her knowledge of the close link with man, often astonished her – for instance when she saw chimpanzees excitedly greet one another with hugs and kisses, or walk together holding hands. She once observed a male chimp greet a female by taking her hand in his and, after drawing it to his lips, kissing it gently.

Her first few months’ study transformed understanding of a species which had previously been assumed vicious and violent. But it was not until she established that the animal was a meat-eater that the scientific community began to take notice.

Goodall’s second big discovery caused greater excitement – when, in her fifth month of study, she watched the chimp she had named David Greybeard fishing for termites with a twig he had specially fashioned for the purpose. Until then, it had been thought that what separated man from the animals was his ability to make tools.

But, as Louis Leakey wrote to Goodall on hearing of her discovery, “scientists holding to this definition are faced with three choices: they must accept chimpanzees as man, by definition; they must redefine man; or they must redefine tools.” Today, man’s ability to communicate by speech is taken as his chief distinguishing characteristic.

Although she had already greatly increased understanding of chimpanzees’ sleeping and feeding patterns, Goodall still knew little of the animals’ social behaviour. That began to change in Spring 1961 when she found that the chimps were no longer afraid but seemed almost to be threatening her.

As she described in The Chimpanzees of Gombe (1986), she found herself one day being stared at by a large adult male uttering “an eerie alarm call. . . a long wailing wraaa. He shook the vegetation more vigorously and I was showered with raindrops and falling twigs and leaves. The call was taken up by other chimpanzees. All around me branches were swayed and shaken, and there was a sound of thudding feet and crashing vegetation.

“My instincts urged me to get up and leave; my scientific interest, my pride and an intuitive feeling that the whole intimidating performance was merely a bluff kept me where I was. To prove myself utterly harmless, I feigned disinterest and pretended to chew up leaves and stems.”

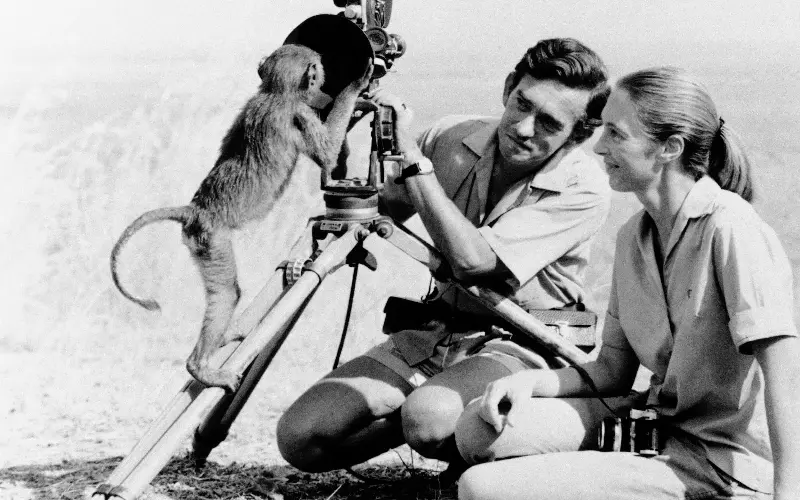

Six months later the animals’ aggression stopped as swiftly as it had begun and she was able to follow them in all their daily doings. She became a close participant in many of their rituals and was recorded by her future husband, the Dutch photographer Hugo Van Lawick, tickling infants and grooming adults.

National Geographic television specials captivated viewers and, by increasing public interest in her work, ensured its future funding. In 1964 her modest camp became the Gombe Stream Research Centre and a favoured destination for ethology students.

By the early 1970s Jane Goodall had amassed plenty information confirming her belief that chimpanzees were similar in many ways to humans but “rather nicer than us”. She was thus particularly disturbed when the community she had been observing began to divide and, in 1974, declared war. After four years of outright aggression, the “Kasakela” community had utterly annihilated the “Kahama”.

“Suddenly,” she wrote in Through a Window (1990), “I found that under certain circumstances they could be just as brutal, that they also had a dark side to their nature.”

The violence was mirrored in her realm when in May 1975 four of her researchers were kidnapped by Zairean rebels, and she had to flee to Dar es Salaam. There she was horrified to hear from her field assistants that a mother and daughter chimp had attacked another female who had just given birth, had wrenched the infant from its mother, killed it and eaten it.

The infanticide continued until 1977 when the aggressor-mother had another child of her own. As well as being hard for Jane Goodall to stomach, these events brought trouble in that she was accused of inventing them for the sake of publicity.

She had been long used to jibes from the scientific community, which considered her approach too anecdotal and sniffed at her custom of giving the chimpanzees names rather than numbers. She tended to ignore admonitions even from her supervisor at Cambridge. In 1965 she became only the eighth person in the history of Cambridge to receive a PhD without having first a BA.

More recently her methods have been fully vindicated and provide the standard against which other observational techniques are measured. According to Roger Fouts, a psychologist who studies the chimp’s linguistic abilities, “her work is almost comparable with Einstein’s.”

Long recognised as the foremost authority on chimpanzees, in the 1980s she turned her attention to the plight of the mammal worldwide, in laboratories, circuses and zoos. In 1986 she and some others founded the Committee for Conservation and Care of Chimpanzees. She became the principal spokesperson, making many media appearances.

Her many other books included her autobiography, Reason for Hope (1999) and several works for children.. Publication of her book Seeds of Hope: Wisdom and Wonder from the World of Plants, co-written with Gail Hudson and scheduled for the spring of 2013, was delayed for a year after an early review identified several instances of plagiarism: Jane Goodall subsequently apologised for her “chaotic note-taking”.

Jane Goodall was appointed CBE in 1995, advanced to DBE in 2003. In 2006 she received the Legion d’Honneur and a UNESCO medal, and in 2021 the Templeton Prize. She remained dedicated to her work as scientific director of the Gombe Wildlife Research Institute while also lecturing widely on environmental issues. She died while visiting California on a speaking tour.

Jane Goodall married Hugo van Lawick in 1964; they had a son. The marriage was dissolved in 1974 and the following year she married Derek Bryceson, the only white member of the Tanzanian parliament, who died in 1980.

Dame Jane Goodall, born April 3 1934, died October 1 2025